I don’t remember much of my childhood. It’s kind of sad, and honestly a little scary when I dwell on it. All of that time spent developing and growing up, and it’s nothing but a patchy series of half-memories to me! I was so unaware of how important and yet temporary it all was — and really, we’re all guilty of this. It’s retrospective thoughts like these that lead adults to get on one knee and drop meaningless pearls of wisdom to 8 year olds that “childhood doesn’t last forever,” and that “you’ll miss this,” as if the kid is suddenly going to develop some constant temporal awareness that allows them to perfectly savor childhood so that they won’t grow up saying the same shit. We struggle to comprehend ourselves and where we came from. We vaguely recall growing up, but only from a more world-weary vantage point where we almost speak about our past experiences apologetically. But right now we at Reed are more focused on retaining Deleuzian critical theory and chemical equations to dwell too much on how uniquely odd it is that we even got to where we are. So what’s to be done about it?

Probably the closest I’ve come to feeling resolved about this issue of aging was in the ecstatic yet devastated state I found myself in walking out of the movie theatres after watching Richard Linklater’s latest and most ambitious film to date, Boyhood. My head was racing so fast trying to process what I had just watched that I burned my hand trying to light my cigarette and hardly heard my friend when she asked, “So, what’d you think?” … What did I think? Wow. What DID I think?

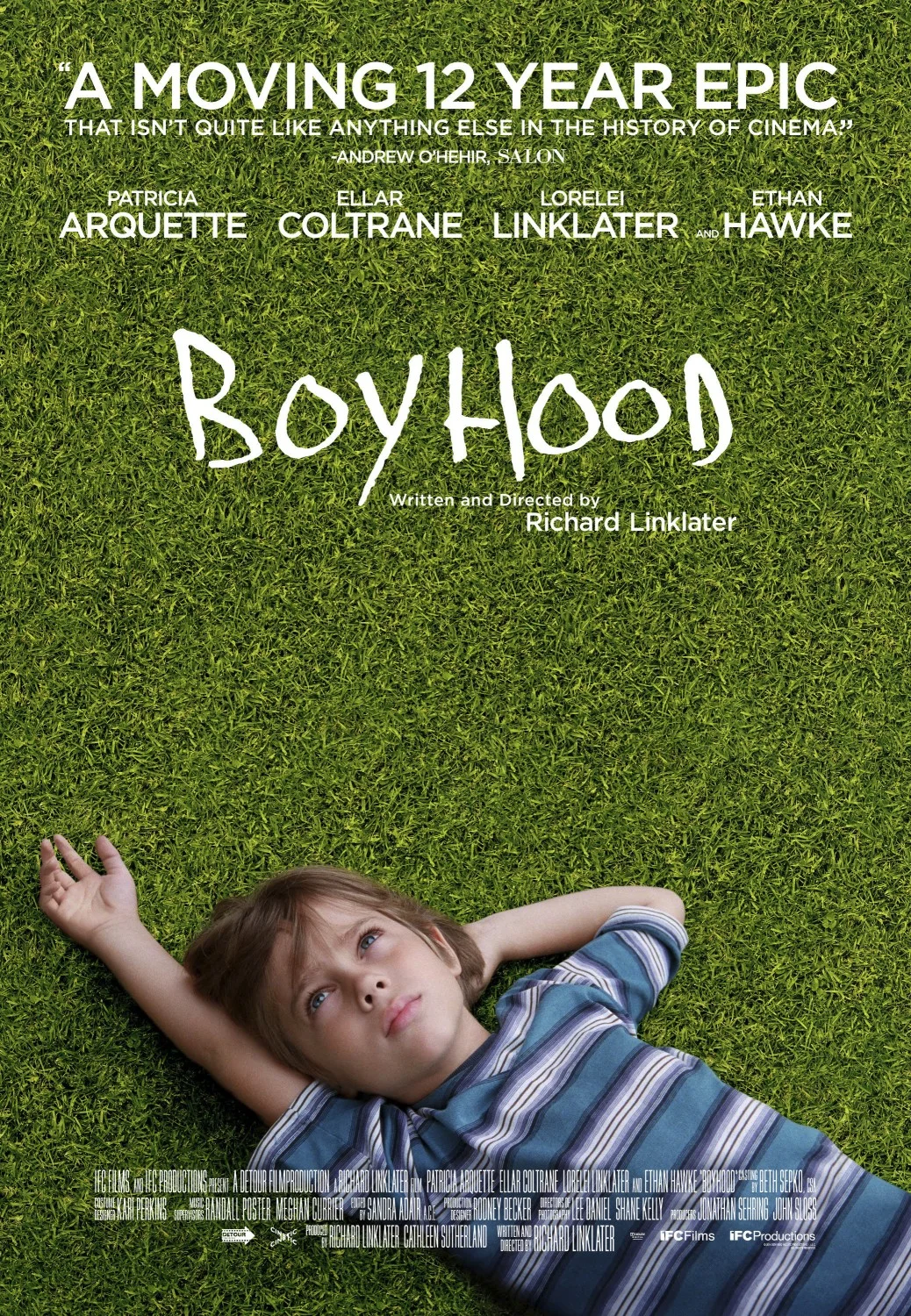

I’ll try to answer that question later. For now, let me explain what this film is about. The movie itself is really a simple series of glimpses into the life of a boy, Mason, from Texas as he grows up with his mother and sister. The narration starts in 2002 with Mason as a six year old and ends with him as an eighteen year old 2013. Along the way, his single mom (the ever-amazing Patricia Arquette) dates one alcoholic loser after another, his biological dad (Ethan Hawke) comes back and tries to reconnect with him, and he smokes some weed. With a cursory regard, it’s a simple, patient slice-of-life drama.

But obviously, it’s more than that, otherwise I wouldn’t be writing about it, right? Right. Because the next thing you should know is that Richard Linklater actually shot this film over the course of twelve years, and we’re actually seeing Mason and his sister grow up. That pudgy confused kid at the beginning and that gangly mellow ‘Gen-Y’er are both played by the same Ellar Coltrane, only years apart. Mason is Linklater’s Antoine Doinel, condensed into a single 2 hour 45 minute film. This begins to explain the utter scope of Boyhood’s project, but its the truly anthropological whimsy of how the movie investigates our generation that the true genius lies.

Linklater employs an almost Yasujiro Ozu-like patience with the development of his characters. The camera movement is simple, allowing the characters to exist and develop on the screen with patience and revery for the modern daily life. Jumps in time are lucid and sometimes even undetectable, and the dynamics of adolescence unfold before us. Maybe this is why the film almost felt like a gift from Linklater to our generation -- a magnum opus that we can watch and rewatch with that same sense of familiarity.

Familiarity. Maybe that’s why I’m so stoked on this movie. Everything felt so familiar, and I felt completely at liberty to project my most personal experiences into each scene. The petty sibling fighting, the half-hearted teenage promises to my mother that I won’t drink, forming crushes, being called a “faggot” in middle school, all of it was there on the screen. And even when a scene didn’t specifically resonate with my experience, the pacing was so perfectly crafted that I empathized with the situation. Watching the boyfriends of Olivia, Mason’s mother, descend into repeated patterns of alcoholism and abuse was almost sickening to watch because it was so REAL, almost like it’s anti-cinematic in how domestic abused is portrayed.

Linklater is undeniably appealing to nostalgia, especially with his occasional and admittedly ham-fisted insertions of “remember-when” pop-culture references, but at the same time (and almost paradoxically) his portrayal of the March of Time is profoundly unsentimental. People deteriorate and reveal the monsters they were hiding all along, friends are more disposable than we first think, and fights go unresolved. Perhaps the best example of this anti-cinematic and hyper-realistic tendency is how Linklater lets characters drift in and out of the narrative, often with their “fates” left unknown to the audience. Most of the main characters’ last appearances on the screen are frustratingly ambiguous and don’t give a sense of “closure,” but that’s because people enter and leave OUR lives just like that, and sometimes its fine but other times so, so sad. Fuck what determinism has to say, because shit happens. This ambiguity also reminds us that the last time we see these characters is by no means the end of their story, and their lives don’t end the moment they’re no longer relevant to the protagonist. This is the closest cinema has come to reconciling narratives with the unpredictable and often anti-climactic nature of real life.

To that end, I’d like to reference a particular scene where Mason’s mother has a heartbreaking argument with her daughter Samantha after leaving another boyfriend: Samantha asks, “Why are you crying?” and broken down, all she can respond with is, “Because I don’t have all the answers.” I think that’s a great way to understand Linklater’s project. Boyhood doesn’t have the answers, but at the very least it can show what it does know. And what it does know is that life is sometimes devastating, sometimes boring, and sometimes even pretty cool. Because sometimes people don’t deteriorate and they stick around and better themselves.

But let’s stop here to bring this article back to my friend standing on the curb outside the theatre, asking me what I thought. If I’m being real right now, my literal answer was probably something like, “Yeah, wow, it was like reeeeally good,” but nothing I said would have felt satisfying. So here’s what I’ll leave it at: Boyhood helped me remember, but it also helped me understand why I want to remember. We are constantly re-discovering and re-evaluating and re-assessing ourselves in order to comprehend life, whether as a little boy laying on the lawn of his elementary school or as a college boy hiking in the mountains on ‘shrooms. And Linklater did an amazing job of capturing that for us, so do yourself a favor and go see it.