Most Reed students have heard tales from Canyon Day’s past, when the celebrated century-old tradition meant something entirely different than it does today. From unsolicited lake crossings to burning native vegetation, the Canyon suffered innumerable blows at the hands of Reed students and staff members alike. All this effort was, of course, an attempt to “tame” the natural space and convert it into a park more reminiscent of Victorian-era Hyde Park than 1920’s Portland. As David Mason’s ’58 Biology thesis cites, even early on the College had a fascination with altering the natural area. According to him, the Reed College Record in 1912 stated: “through the center of the campus, east and west, is a wooded ravine, which, in the course of development of the grounds, will be made a picturesque lake.” I know the lake is picturesque now but the early Reedies had a drastically different take on what the word picturesque meant. Canyon Day aside, none of the misdirected machinations of students during the early 1900’s compare to what is arguably the most destructive construction project to be completed in the Canyon: the community pool.

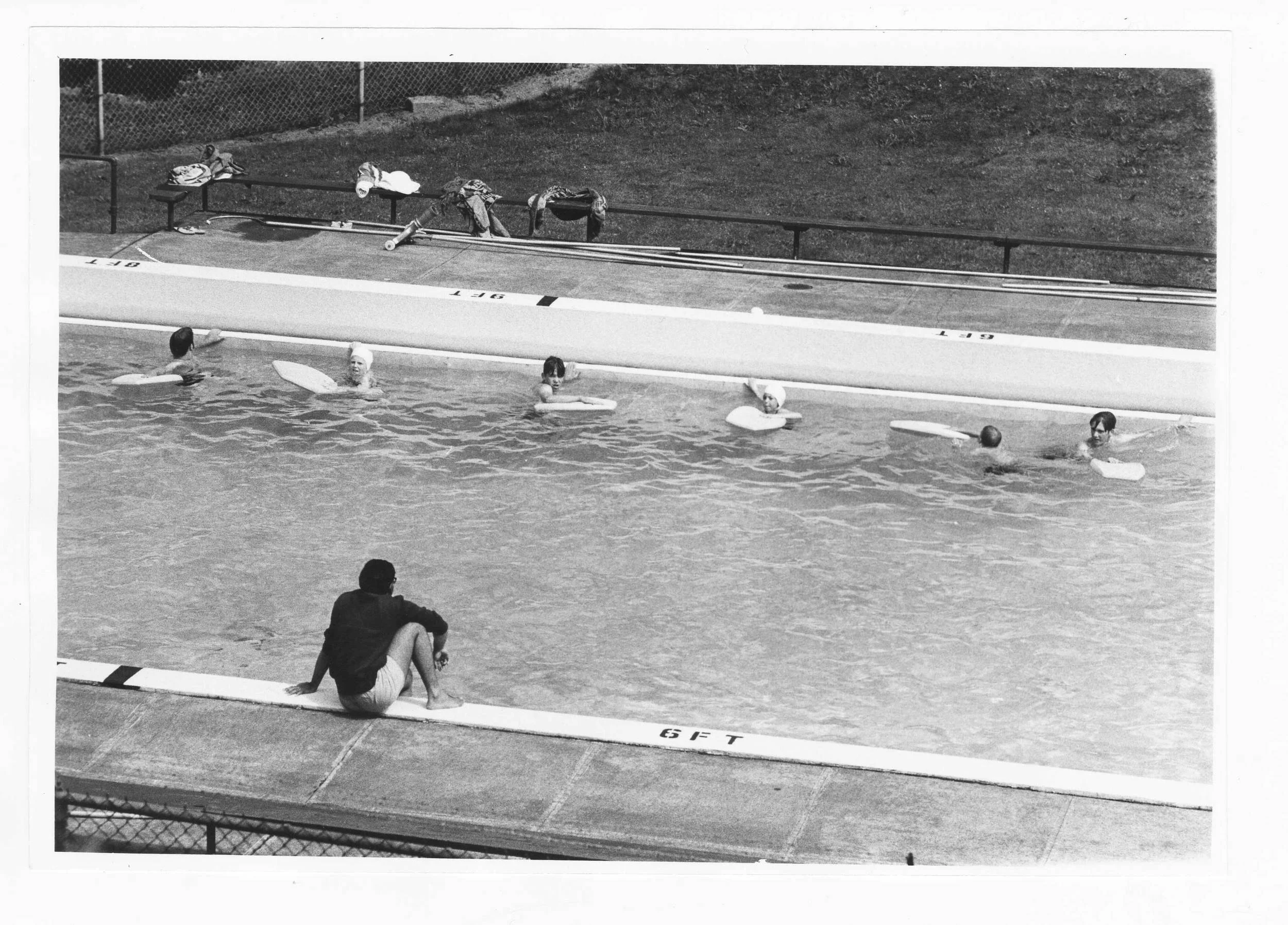

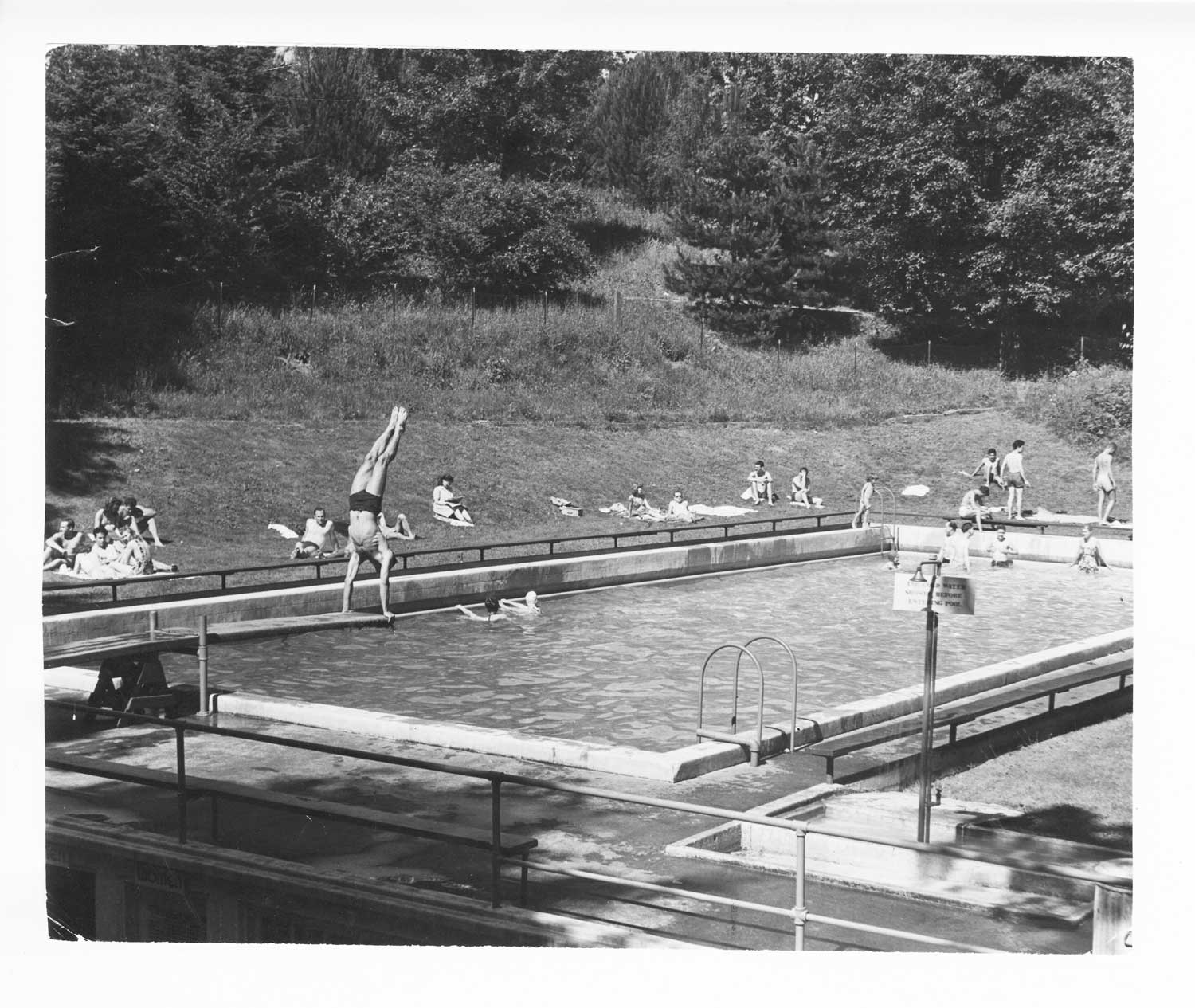

Although not the most outwardly malicious civil engineering project, the outdoor swimming pool proved a major diversion for the course of the stream and severely hindered the ability for wildlife to call the canyon home. Set in concrete in 1929, the outdoor pool had existed in some capacity for many years before. On Canyon Day in 1915 students hand-dredged a 10-foot-deep hole in the west end of the natural pond. They wanted a place to swim. The addition of a dock and bathhouses sometime later further solidified the area as a place for swimming. Years after the impromptu swimming hole construction, a 10-foot-tall earthen dam was built just west of where the land bridge is now. This diverted the flow of water coming out of the end of Reed Lake and allowed for the construction of the concrete-lined swimming pool in 1929. Extending from the earthen dam to the Physical Plant Canyon staircase, the pool area was delineated by a barbed-wire fence and surrounded by a grassy lawn on its north side. Lake water was directed through underground pipes that emptied out downstream of the pool.

The excavation necessary to produce the swimming pool introduced large amounts of silt into to water which damaged the local ecosystem. Introducing silt and excess nutrients into the water increased the speed of eutrophication. Setting aside the exact biochemical mechanisms for lake eutrophication (also known as hypertrophication), the end result was a lake depleted of oxygen with a shoreline more susceptible to invasive species. This was one of the factors allowing the riparian zone (the land-area immediately surrounding a body of water) to become overrun with English ivy, a problem that is still being dealt with to this day. Reed student and prolific canyon writer Jimmy Huang ’97 cited the construction of the outdoor pool as one of two major events leading to excessive sedimentation in the lower Canyon. The other was the construction of the Cross Canyon dorms beginning in 1957. That construction marked the first campus development north of the Canyon, which is technically true, since the swimming pool was in the Canyon. In addition to sedimentation, the water from the lake was diverted through a large culvert on its way downstream. According to the Reed Canyon Enhancement Strategy of 1999, the fish were unable to pass through the culvert “due to its slope and the vertical drop from the concrete pipe spillway to the creek bed.” Characteristics of the Canyon taken for granted today —the steelhead trout and diverse riparian zone— were rendered impossible by the placement of the pool in that location.

The swimming pool remained in moderate use throughout the years, undergoing a renovation in the late 1950’s, but with the construction of the Watzek Sports Center in 1965, the students that did use the outdoor pool moved to the indoor pool which still in use today. It turns out that during the September to May academic year, the student demand for an unheated outdoor swimming pool in Portland drops significantly. Neighborhood residents mostly used the pool and the “Picnic Area” lawn during the balmy summer months.

By the turn of the millennium the pool had mostly fallen out of use by students and was deemed irreparably damaged. Simultaneously, the City of Portland designated, via its environmental zoning laws, that the Canyon was a protected R5p and R5b zone limiting future alterations to the area. The pool would cost more to repair than to remove, so in 2000 the ground was uprooted once again and the area that had been home to swimmers for nearly 70 years was demolished. On June 27th, 2001, the Portland City Council approved a plan to restore the Johnson Creek watershed, concurrently with the beginning of Reed’s Canyon Restoration Project. The Crystal Springs Headwaters Fish Passage and Restoration Project, the objectives of which can be found online (http://reed.edu/canyon/rest/overview.html) aimed to restore the Canyon to pre-college conditions that would allow for fish, birds, and natural vegetation to flourish as they had before 1900. Through summer and fall of 2001 the fish ladder was constructed, opening to champagne uncorking and joyous revelry on November 16th, 2001. The 85-year hiatus for fish was finally over.

The Canyon you see today has undergone a complete transformation in the last fourteen years. With a renewed city-wide political focus on environmental stewardship, dedicated Reed staff and students have steadily been fighting the ivy hoards and erosion that once had all-too-large an impact of the landscape of the Canyon. Fish have returned to Reed Lake, with otters, birds, and amphibians close behind. Another curious change has occurred within the student body. Before where there was a space for poolside relaxation, now is a perfect natural laboratory for academic study. From the construction of the dam in 1929 to its demolition in 2000, only 21 senior theses studied the Canyon and it’s ecology. From 2000 to 2005, there were 14. Where once there were only humans enjoying the Canyon, now there are all manner of wildlife.

This year, Canyon Day is on Saturday, October 4th. Meet near the land bridge; right next the old footprint of the community pool.