The hand-drawn work of scribes has always had an inexplicable allure. Since the time of Gutenberg, typographers have been attempting to imitate their intricate and elegant lettering. The scribe’s pen or brush was then seen as the higher form to which type designers aspired but could not hope to achieve, and even today it still serves as an important tool in the typographer’s kit. In the words of Jan Tschichold, a German type designer and calligrapher, “Anyone who has ever done lettering by hand knows much more about the qualities of right spacing than a mere compositor who only hears certain rules without understanding them.”

Calligraphy has long been known to be the graphic design equivalent of life-drawing. “They only admit students to art schools who show proficiency in drawing, even if they’re going for photography. The same principle applies to calligraphy. It develops a sensitivity to space, develops that for designers. When you learn calligraphy you become attuned to the spacing and layout,” says Lance Hidy, designer of the Penumbra font and graphic design professor at Northern Essex Community College. Hidy grew up in Portland where he was influenced by the teaching of Lloyd Reynolds (English and Art History 1929-69). Today, that legacy is threatened. As digital tools have become more abundant, everyone and their brother thinks they can design typefaces. Reborn traditions like Reed’s scriptorium help keep the essential link between calligraphy and typography alive.

Meeting Orphan Annie

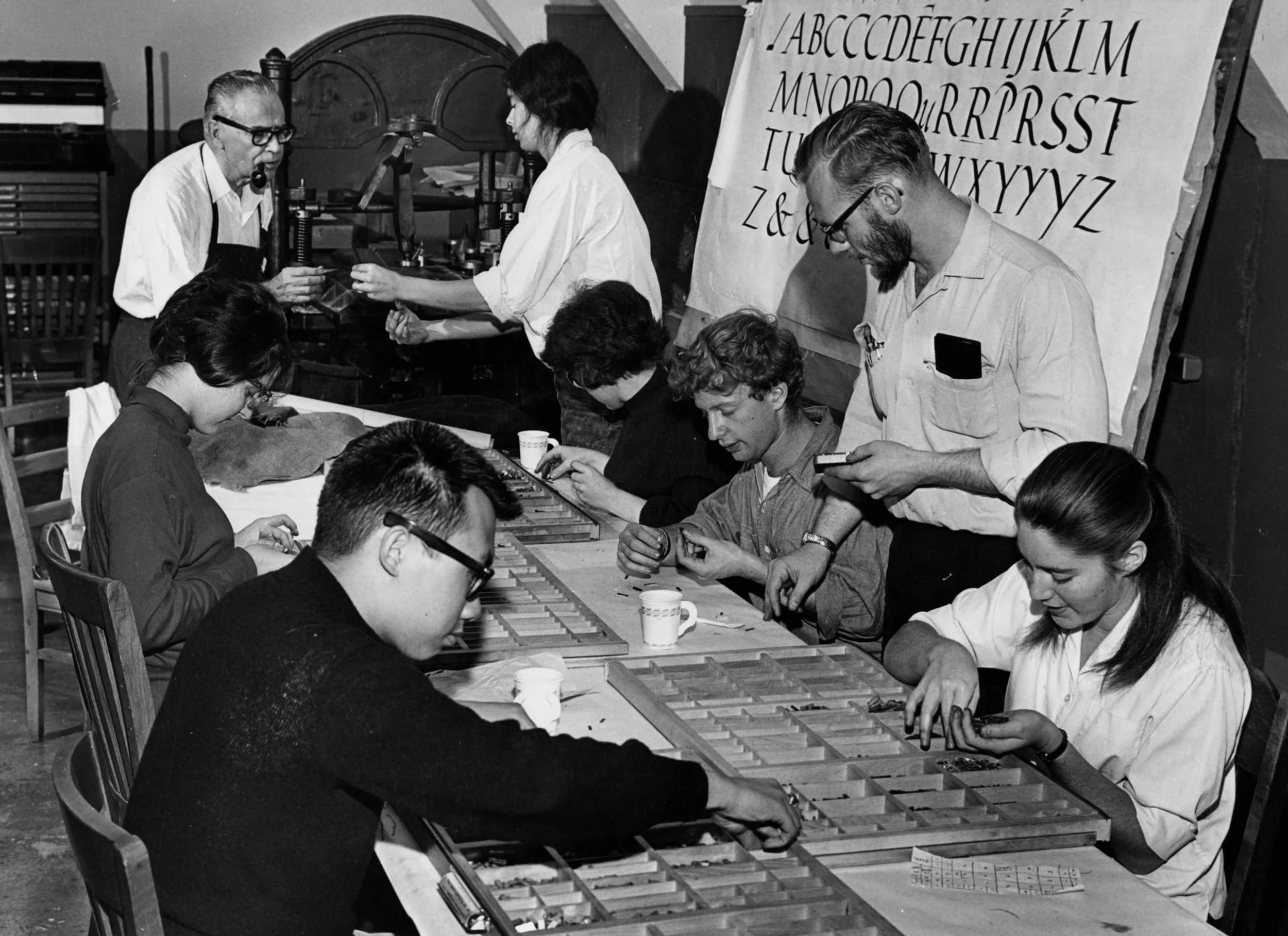

During Paideia, along with a full suite of calligraphy classes, students were led on a scriptorium-sponsored trip to the C.C. Stern Type Foundry. The Foundry is a museum of metal typecasting, as the field has been relegated to small-press printing operations, if any place at all. Yet before computers could be used for typesetting, the primary means of getting the word out in the 20th century was by using type-making machines called casters, which were on display at the foundry.

For a page of text to be printed, first the type for it has to be cast. One such caster is nicknamed an “Orphan Annie” because it only produces one sort — one size of one character of one typeface — at a time. This process is done by pouring lead into casts arranged by compositional matrices.

When we saw the Orphan Annie on tour we all shrunk away slightly from one of its spouts, which brings forth a smooth arc of molten lead when pressurized.

Other monotype machines, capable of producing sorts of greater variety, are also on display at the foundry. However, the most useful type of machine for publications like The Grail and The Quest, before offset lithography printing came into its heyday would have been a linotype machine, which allows for entire lines of texts to be imprinted on a long, square piece of metal known as a slug. Using the machine at the foundry, you would simply type the line of text on a keyboard in front of the machine and watch as the gears and levers of the machine clicked each letter into place on the slug.

Dr. Puterschein and Mr. Dwiggins

Once the type has been cast it’s sent off to one of a few small press printing operations that still use letterpress machines for their book designs. The interplay between these two disciplines is interestingly spelled out in the letters to William Addison Dwiggins, from his alter ego, Dr. Puterschein (German for “pewter shine”). Dwiggins was a type designer from the early 20th century who created Puterschein as a caricature of the type of thinking that must have plagued Dwiggins as he attempted to work with those who set metal type. Dwiggins coined the term “graphic design” in these satirical letters which showcases his dislike for working with metal type casters.

“I am able to say without any hesitation whatever,” claims Puterschein, “that the features of his style which appear ‘contemporary and original’ are results of his association with me. Left to himself he would have gone on as he started: a student of historic design, conservative, timid.” Puterschein, speaking on behalf of the typesetters of the modernist era, believes that the design achievements of the day were primarily due to technological advances made by people like himself and not the artistic talent of designers like Dwiggins.

“Modern aesthetic…” Puterschein continues, “denies that anything is shaped by human hands — that anything possibly could be shaped by human hands. Its very life-source is a strenuous and perpetual denial of fact that any such soft mammals are alive on earth. Its life is a life of metal; hard, square-edged, unyielding. It turns away in disgust from suggestion that any material object could grow, or be punctured, or eat, or bleed, or digest…. [Dwiggins’ designs] try to straddle the two worlds, the old and new…. And of course they fail to grasp the implication of the new age of machines and metal. They insist on dragging man into the formula — and on dressing him up in a fancy costume of triangles and other geometrical absurdities — thinking that they have thereby fulfilled all the requirements of the ‘modern’ style. Is it not so? The brass works of an alarm clock could make better modern designs than these emigre Victorians.”

The title page of a monograph held in Special Collections reads, “Dear Lloyd [Reynolds] — in answer to your plaintive request (last newsletter) for any news about the good Dr. — I hasten to enclose the last we heard from him in Beaumont [Texas]. Sorry its not exactly current, but its unmistakably [sic] the Dr.”

It is easy to imagine a back-and-forth among the designers and calligraphers over the looming threat of mechanization and their thoughts about the contemporary state of book design and layout. The Putenschein monographs not only offer an opinion in direct opposition to the views of Dwiggins and his contemporaries, but also stand in stark contrast to the type of teaching Reynolds conducted in his calligraphy classes.

Master and Apprentice

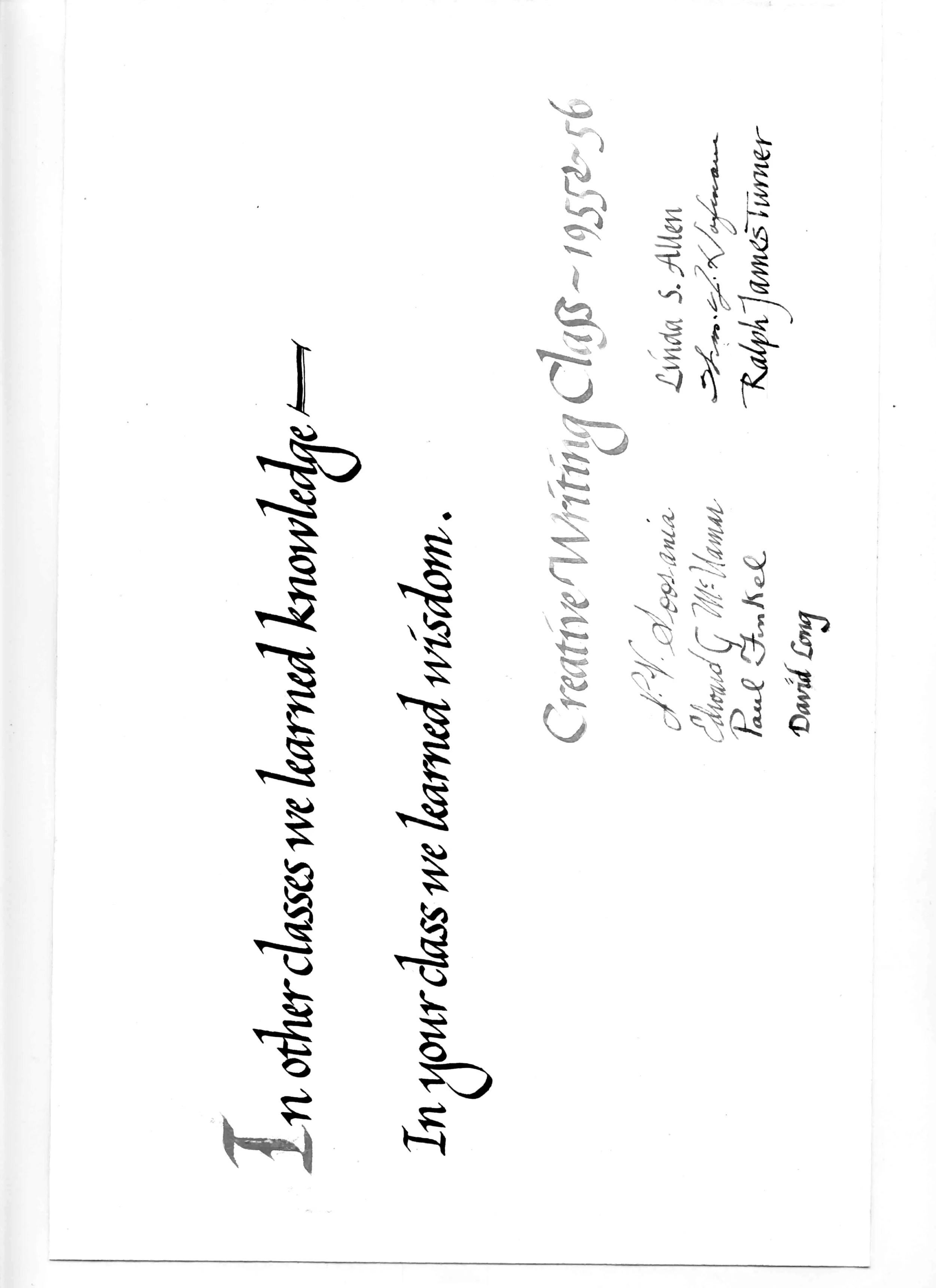

Reynolds gave a series of workshops at Haystack Rock during the summers. The notes from the last of these workshops — written out in a smooth italic by Hidy — are preserved in the Reed Library’s Special Collections. Reynolds implored participants to “caress the letter with the pen as though you think the police should stop you,” to, “have a sensual orgy” and to “think of meaning, not just the pen. You are writing ideas not letters.” Sumner Stone ’67, head of Adobe’s original design team and operator of his own type foundry, reminisced about the teachings of Reynolds in a 2014 article on the Trajan typeface he designed. According to Stone, the calligraphed letters produced during his time at Reed, “would be examined not only for their correctness of detail, but even more importantly [for] whether or not they embodied the quality that Reynolds called ‘life movement’. He told students in his art history class that this characteristic is what imbues letters with spirit. It is what brings them to life.” Similar rhetoric occupies a place in the minds of all young calligraphers serious about their work, and in Reed’s calligraphy Scriptorium, where scribes attempt to breathe life into the words they are writing.

Today there is not much communication between letterpress operators and calligraphers. This is in large part due to the fact that letterpress printers are using ideas developed for digital printing in their analog print rather than taking cues from more time-tested arts. “People that work with metal are dying off and their ideas are dying off with them,” says Hidy. This is why the C.C. Stern Type Foundry functions largely as a museum: their output is small, and while there has been a proliferation in the number of letterpress workshops in recent years, there simply isn’t that much demand for metal types. “What attracted many of us to the digital medium early on,” says Hidy, “was that the computer had brought together all the different tasks — brought them back to an individual person.” This is why the jaded ex-Quest editors of Olde Reed still bear a grudge toward the Paradox for taking over their old office and shunting them down to the basements of the GGCs — they were doing what they would call ‘real layout’ rather than the streamlined practice of using Adobe InDesign as campus publications now do.

The scribe can make adjustments to the page with greater freedom than the typographer and doesn’t have to deal with middlemen — type foundries, printers — in forging his own vision of the best possible layout. It was this freedom that many early adopters of design technology sought as type designers and graphic artists, allowing people to see the whole page as their individualised creation, minimizing the separation between artist and product. Hidy states, “It can justly be said that any carefully prepared piece of writing has the possibility to surpass a piece of print in respect to elasticity, sharpness, decoration, and, indeed, personality.” The earliest type designers, working in 15th century Italy, worked hard to produce facsimiles of the writing of scribes of the day.

The printed book offered advantages of mass, and consequently cheaper, production allowing more people to gain access to the literature at hand. Hidy quotes Stanley Morison, a historian of type design, saying, “…it needs to be admitted that, admirable as are Jenson’s printed letters, they are less beautiful than the written characters of Sinibaldi,” an eminent scribe of the time who managed to beautifully blend lowercase and capitals in a way that could not be achieved yet by the earliest type designers like Jenson. The focus of the typeset book was on legibility rather than beauty, but Jenson and others managed to set the standard for printed works going forward. They achieved this by looking to the scribes, whose diligence in refined simple elegance kept them away from embellishments that could otherwise interfere with the legibility of the page and detract from the reader’s experience. Throughout the early years of type design, type designers were able to define their own vision of the page by looking at the work of contemporary scribes.

Typeface in the Digital Age

A shift was occurring at the time Hidy was writing in 1977. Things we now take for granted, like re-justifying lines and being able to rapidly change font size, were seen as novel introductions to the fields of book layout. What had once taken meticulous reworking could now be achieved quickly and easily. According to Hidy, “the use of computers and video-screens in photo-typesetting have practically given typographers the scribe’s flexibility in placing letters on the page.” Hidy notes that while magazines and journals were the most adventurous in their use of these new techniques to create more engaging layouts, book designers were using them often to mimic the types of design that could already be accomplished using metal. The convention of indenting at the beginning of a paragraph, for example, was inherited by our digital age from the era of widespread metal typesetting. In the 15th century it was often seen as more visually appealing to leave part of the line to begin in the margin. In their choice of fonts, they also stuck to those previously used in metal typesetting, but the new methods sometimes made the old scripts appear spidery and broken, creating a need for new alphabets to be created from the new mechanisms.

This was what led Adobe to come up with their Adobe Originals series in the late ’80s and early ’90s, designing new fonts for use in their programs. The creation of one of these fonts, Trajan, is chronicled by Stone, the head of Adobe’s design team at the time, in the 2014 essay quoted above. Trajan was not a typeface based on those of earlier times, but in the ancient Roman inscriptions found on surfaces like Trajan’s column from ancient Rome, or more pertinently, the entryway inscription above Eliot Hall.

Eliot Hall: Home of Inspiration

The story of the Trajan typeface begins during Stone’s time at Reed in the late 60s, as he watched Father John Catich, at the time the foremost practitioner of Roman letterforms, engrave the words “Eliot Hall” into our very own building. Later, in the ’80s, Carol Twombly, working for Stone at Adobe, digitized and reworked the lettering from Catich’s books as an Adobe Original called Trajan for use as a display font that has gained in popularity since its inception, being widely used today.

Stone gained an interest in his field through his calligraphy classes at Reed, taught by Reynolds, and began his work as a type designer under the tutelage of Herman Zapf, one of the most prominent and prolific calligrapher/typographers of the 20th century. Zapf taught himself calligraphy at a young age using a book of Edward Johnston’s that has since come to be known as the calligrapher’s bible, and designed upwards of 60 typefaces over the course of his illustrious career.

“I looked to see if there was any place I could work to do my calligraphy and lettering. Zapf had just been hired by Hallmark Cards,” says Stone, “and I sent in my portfolio. Two or three people were making typefaces from proprietary hand-lettering, custom designs from Herman Zapf, and it was my first exposure to type design. I was thrilled to be there and watch, and spent time doing fancy lettering for Mother’s Day cards.”

Throughout his career in the type design, Stone has seen the trends in calligraphy and lettering change. “Before any of the calligraphy groups got started, calligraphy was primarily taught by Lloyd and his students. During the ’70s it was a big phenomenon, in large part due to Jackson, the queen’s calligrapher. He was very active in saying that people should start groups.” The Society for Italic Handwriting started, and one of Lloyd’s spinoff groups, The Order of the Black Chrysanthemum (named for the shape an ink-stain makes when a pen explodes in breast pocket), gained popularity. Stone even helped start a group of his own in the San Francisco area where he was working at the time.

“The interest in type design as an academic field is very new,” says Stone. “Cooper Union, a small, prestigious school in New York, is the first to have a graduate program in typeface design. I’m teaching.” A grounding in calligraphy and lettering is essential to such an enterprise, but the approach has changed slightly from the time when Stone was taking classes from Reynolds at Reed. According to him Reynolds didn’t like type very much and was more interested in the movements of the brush or pen on the page.

“The handwritten letter has a certain presence,” says Stone, “the thing Lloyd was entranced by was the movement of the form as something you see that’s very appealing. When you see good calligraphy your brush starts to move again.”

“When I started looking at type it seemed like a base imitation of calligraphy. Handwriting was lost. They were no longer influenced by the fact that they were calligraphers. In the digital age there are a lot of those restraints, making it more calligraphic in a certain way. It’s much more possible to do the nuanced approach of the written form. Yet, there are things you can do with calligraphy that you simply cannot do with type.” The influence of calligraphy and lettering is always there, but, Stone notes, “we use typefaces that are not directly based in calligraphy. When you make a typeface that is strictly based in calligraphic forms it has, by its nature, a limited use because it’s not part of mainstream typography.”

A Never-Ending Legacy

Even without the widespread use of calligraphic fonts, there is still an inherent value in studying calligraphy for any typographer. “Using type is a fundamental to graphic design and the first thing to know is where the letterforms come from, how to make them, space them, get them on the page. The top type designers have a very strong grounding in calligraphy,” says Stone.

“I had already graduated and went back to school to study calligraphy, I had friends who learned calligraphy in helping me to learn it. When I was at Reed College, my father was a college professor, I felt like there was something missing in the pure academic atmosphere, I really wanted to connect the intellectual with the physical and physiological world in a way that was really missing in the classical liberal arts education. Calligraphy was a way of doing that, the substance, the physical form of language, it’s one of those things that I still find magical. The study of writing and its history is very new and fascinating and has not focused on the visual part of the letters like it could. We’ve ignored the subject in our colleges and universities which is a shame because it’s a rich subject that can lead you in many interesting directions. In this younger generation there seems to be a lot of interest in letterforms in their own right.”

Hidy seems to be thinking along the same lines as Stone, as he has begun taking a more nuanced approach to the display of information in his classes at Middlesex Community College in Haverhill Massachusetts, incorporating ideas that are perhaps unique to the digital information age. “I went to Yale and all the people I associated with were verbally astute people who excelled in their studies,” When I started teaching at college, I suddenly had students on the other end of the spectrum, people who had disabilities, or spoke English as a second language, people that didn’t understand how to use books. I asked them to redesign the page. Started them with 11-point type and put in pictures and sample artwork. The assignment used to take multiple four hour classes; the new approach not only improved the graphic design, but the students completed the work in two classes. That was a major turning point for me as a graphic designer. The world shifted, I was on a different plane. I had to rethink everything.”

What matters to Hidy now is whether comprehension happens, and he finds this indicative of a larger cultural shift, citing the widespread use of emoji as evidence. “The focus on type and calligraphy will always be a part of our cultural heritage, now if you want to be seen literate putting a bunch of phonetic images together on a line is going to be viewed as one of the worst ways to communicate.” The biggest barrier for Hidy and others looking to utilize new ways of communication that bring in more than mere phonetic symbols is the old guard of educators who are unlikely to embrace a more heterogeneous approach to communication. According to Hidy, one of the reasons it took so long for graphic novels to be embraced by the publishing industry was because of the restrictions of movable type. Digital technology has made the process easier, allowing for approaches like Hidy’s.

Hidy has also adopted this approach in simple everyday text. There has been much debate over whether serif or sans serif fonts make it easier for people to comprehend the words on the page. However, based on his own research Hidy has concluded that the distinction should really be between monoweight or tapered typefaces - those that those that are uniform in stroke weight throughout, and those that have higher degrees of contrast between the widths of different strokes, respectively. “Just because you’re used to a certain type of typeface does not mean its more legible, it just means you’re used to it. Caecelia, a monoweight font, is default for the Amazon Kindle. It still has the serifs to appeal to the traditionalists, but also the monoweight for improved legibility.”

Even with his new findings on what is most easily comprehensible, Hidy is still focused on what is the most visually appealing. Advocating for an approach that takes into account both ease of use and aesthetic beauty, he compares the graphic arts to fly fishing, his other passion in life: “The goal of fly tying is to get the trout interested, and even excited. When a well-designed fly mimics the aquatic food that trout eat, and is presented in a believable manner in the water, the trout will consume the fly. Likewise, graphic designers try to interest or excite readers, to get them to stop whatever they are doing, and to consume the offered content instead. The choice of a typeface is only part of the art. Whether your target is a fish, or a reader, the design and presentation of your offering is not only a challenge, but an art.”

Further Reading

This article draws upon an interview with Hidy and two sources of his, “Script and the Book” from 1977 and “Calligraphy and Letterpress in Design Education,” a lecture delivered in 2005 at The Museum of Printing. Hidy also has a history of type design he wrote for the centennial of the Boston Society of Printers and which is available in Reed Special Collections. The books are interesting not only for the history they provide but because they demonstrate a shift in consciousness from the excitement of the early adopters of technology for graphic design in 1977 to a desire for the older fields of calligraphy and letterpress to have a place in the design education of those utilizing the new technologies. Originally, Hidy seems to take the outlook that the computer, by taking out the limitations of metal typecasting/typesetting and letterpress printing, would bring the book designer closer to the scribe in the way they looked at the page. In 2005 his approach is different, as he credits the advancement of technology with distancing type design from the organic beauty and elegance originally aspired to with type designers who were familiar with the writing of calligraphy and the work of lettering.