The sign is the first thing I see when I wake up and the last thing I see before I sleep. Bland bold letters on a background of bloody maroon, negating my future, telling me this is the best it will ever get, assuring me that this is really an English country estate and not the epitome of everything faceless and inhuman in architecture. This Escherian labyrinth of concrete angles and rotting wood, enlivened only by the occasional hippie tapestry, each apartment an inversion of another, all disintegrating in the drizzle and surmounted by a pair of drifting, deflated balloons, is my castle and my tomb. LIVING IS FUN (but only) AT WIMBLEDON.

It’s not just me. I haven’t been driven crazy by the buzzing eggshell white of my apartment’s walls. The Wimbledons truly are built on broken dreams. Under the sodden walkways, under the sterile leasing office and the littered mud flats, lies the life work of landscaper and Portland legend Andrew Lambert, whose botanical gardens were a city treasure for nearly half a century.

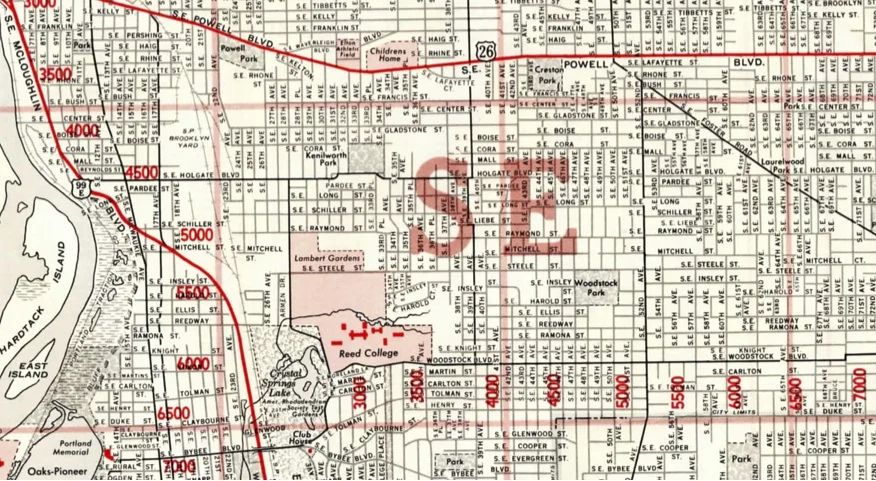

Lambert, a Georgia gardener, first visited Portland in 1925. He was so enchanted by the local plant life that he immediately sold his stake in his landscaping business and moved straight to Oregon, where he lived on SE 28th in the large, rambling house that now contains the Christian ministry in between the Wimbledons and a parking lot. He purchased the surrounding plot of land from Reed to found a garden. “It was a spinach patch” when the college owned it, he recalled to The Oregonian in 1966. “Spinach and carrots. I think Reed College thought they were going to be big, another Harvard or another Yale. They bought all the land around here.”

His small showcase garden soon expanded to cover 30 acres of land – the area that is now covered by the Wimbledons, the Royal Garden and Garden Park apartments, and the Reedwood Friends Church. Lambert believed in providing the public with beautiful gardens that could also serve as inspiration for one’s own home gardening projects.

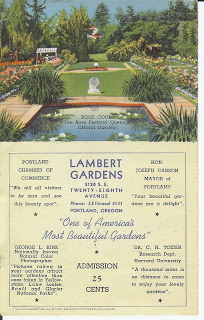

To that end, the Lambert Gardens included a dazzling array of different styles, including English, French and Italian gardens, and a “Vest Pocket Garden” that showed visitors how even a small space could be made harmonious and attractive. “My idea is first to beautify,” he explained in 1934. Peacocks, cranes, and other exotic birds patrolled the walkways (and occasionally strutted off the property: in 1956, The Oregonian reassured workers at the Crown-Zellerbach Paper Mill in Camas, Washington, that the pink bird they’d seen was “not delirium tremens” but one of Lambert’s flamingos). Thanks to careful maintenance, roses bloomed from April to November, later in the season even than in the famous Rose Gardens in Washington Park. Naturally, the queen of the Rose Festival paraded through the gardens every year.

Most of Lambert’s 50,000 to 75,000 visitors a year were tourists from out of town, but that never stopped him from sharing the flowers of his labor generously with his fellow Portlanders. The Gardens’ employees helped create the city’s Halprin Open Space Sequence, a series of parks stretching across central Portland that was entered into the National Register of Historic Places last year. In 1965 Lambert introduced free tours for Portland schoolchildren.

He was kind to his neighbors across Steele, as well. The Gardens provided free passes to Reed faculty and staff, donated floral arrangements for Commencement, and Lambert even provided some tips on beautifying Reed’s outdoor pool area, which we covered in our last issue. (The administration found the idea of covering the barbed wire fence with creeping vines “particularly exciting.”)

By 1968, however, Lambert was in his 80s and could no longer maintain the property. He offered to sell it to the city as a public park, but Mayor Terry Schrunk was not interested. He was forced to turn over his gardens to developers, and the November roses were plowed under for apartment complexes. Over the course of a few months, plants, pots and statuary were auctioned off, albeit somewhat reluctantly. Lambert refused to sell a tree to one couple because a bird was nesting in it.

The December 4th, 1969, the front page of The Oregonian is dominated by a headline trumpeting a reduction in the federal income tax and a picture of a 25-foot-high wave crashing into an Oahu beach. Sandwiched between these national news stories - each vaguely ominous in its own way, but suggesting in tandem an oncoming torrent of Reaganomics and greed - lies a column rather dully headlined “Company starts SE project.” The project, called “Lambert Gardens” after the plants it was due to cover, becomes creepingly and shiveringly familiar to any Wimbledon resident as they read along. Three stories high. Bridges and walkways. An insular “campus” atmosphere. The article concludes with developer Paul Forchuk’s fatuous promise to retain Andrew Lambert’s landscaping. (As well as a comical note: “Rents will range from $135 to $225.”)

The new apartment complex advertised itself with a slogan even bleaker than today’s. “SEE WHAT’S GROWING AT LAMBERT GARDENS”: a grotesque appeal to what it had destroyed that would give any structuralist a field day. The Garden Park apartments that sprung up on the site soon afterward took a similarly stomach-churning approach.

Neighborhood lore has long had it that the Wimbledons were built as a sort of ‘70s utopian singles community. In fact, before their completion, the Lambert Garden Apartments really were apparently renamed Habitats Won and Too. They were billed as a swingin’ home for “sophisticated singles and couples” with “disco 4 nights weekly.” The name was splashed across the newspapers in 1973, when they burned down halfway through construction, and again in 1978 when a Ms. Francine Jefferson was arrested for running a prostitution operation out of them. Her journal, admitted as evidence at her trial, listed her johns by nicknames such as “Bob the fireman,” “7-Up Bill,” and “Race Car Fred.”

By the Reagan era, the hippie monicker had been shed and the property had become the Wimbledon Square we know today. It still relied on racy advertising, though, billing the complex as an “all-adult community” where new leaseholders had a chance to spin a roulette wheel for a $300 cash prize. The whitewashing of the Wimbledons into the purgatory we know today happened only recently.

There are no longer any traces of Lambert’s dreams - or even the unique sleaziness of the apartments’ early days. Lambert’s house is hemmed in by chain-link and mismatched hedges, and the mud puddles and 7/11 pizza boxes of 28th’s gravel sidewalk. The greenery that still remains amid the vertical grays of the apartment complexes belongs in a shopping mall plaza: trimmed with such unimaginative precision that it resembles plastic. Black mold is the last variety of flora that flourishes in the labyrinth. I just spent an afternoon scrubbing it from my walls; maybe the bleach fumes will burn my eyes and nerves enough to let me see Andrew Lambert’s peacocks.