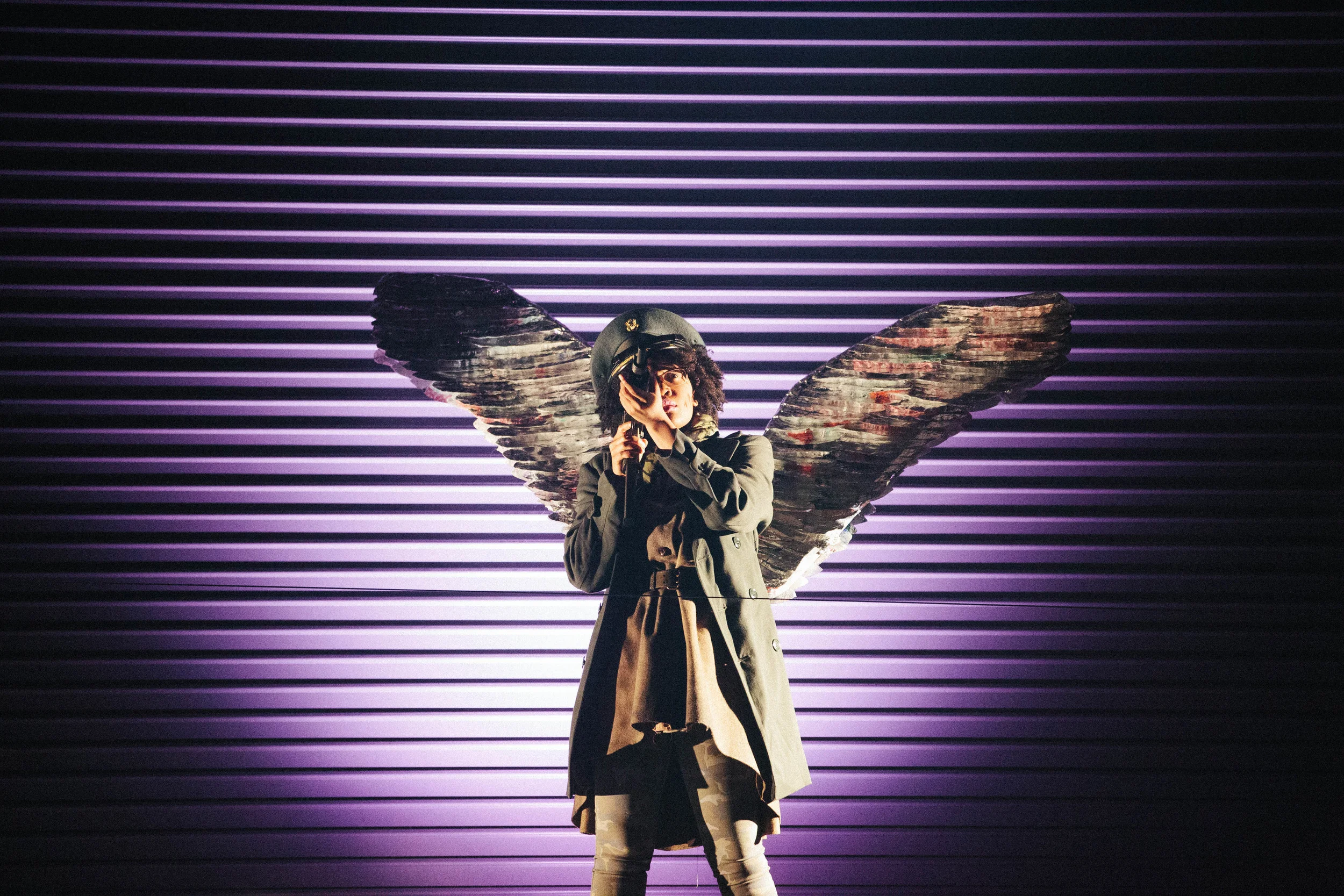

Spread across a piece of clear plastic curtain at the outset of the Reed College Theatre’s production of Jose Rivera’s Marisol, directed by Catherine M’ing Tien Duffly, is the following graffiti: “When I drop my wings, all hell’s going to break loose and soon you’re not going to recognize the world - so get yourself some power Marisol, whatever you do.” As the dark, ominous, bass-heavy music that makes up much of Peter Ksander’s sound design echoes through the blackbox theatre we hear the familiar sound of a spray paint bottle clicking as an angel (India Hamilton) implores the audience to “WAKE UP!” The audience is quickly immersed in Rivera’s dark dreamworld, rendered in all its perverse glory by the stage designers, as the Marisol (Aziza Afzal), a young Puerto Rican woman, narrowly escapes an assault from a man with a golf club (Kevin Snyder) in a shaking and flickering subway into the snowy streets of her home, the Bronx. We learn her guardian angel, the one from the prelude scene, was the one who stopped the man and many others through Marisol’s life as she navigates the dangerous Apocalyptic New York streets. She is leaving Marisol now, going to make war against an aging and senile God whom she blames for causing the environmental catastrophes, economic declines, and widespread war the play takes as its background. Hamilton’s performance is at its best in some of the more touching moments between her character and Marisol. While some of her scheming does not seem to be at the level of anger requisite for war on God, she always brings through the misgivings we should have about even higher order spiritual powers in Rivera’s New York. Marisol’s quest to wake up and see the world for what it really is, is made more difficult by the strangeness of that world and the widespread distrust and paranoia of the people who inhabit it. Not to mention, perhaps worst of all, coffee has gone extinct.

In small ways like this, Rivera inflects his rather bleak vision of New York with humor. As Marisol sits in her Manhattan office, where she works as a copyeditor, a man (Jake Strickland) comes into the office wondering how he’s going to pay for the ice cream cone he’s currently eating and demanding to be paid his royalties from his work with De Niro in Taxi Driver. Often absurd, the play is grounded by the central character of Marisol, aptly described by coworker June (Ashlin Hatch) as a “Puerto Rican Princess.” She continues to pleadingly pray in rhymed verse as the angels of heaven begin to to go to war, and feels tied to her simple middle-class life among all the chaos. The innocence of her character comes through well in Afzal’s performance, as she continues to to display her illusioned sentiments in the seemingly safe confines of her Bronx apartment, praying and holding out for a benevolent God until her world is desecrated, partially due to her realization that she has to fend for herself in the self-indulgent world of paranoia and fear that Rivera has created. The introduction of Lenny (Mike Frazel), a tinkering man-child obsessed with Marisol only from what he has heard from his sister June, brings absurdist humor and New World Order type of conspiracy theory. Within the magical realism of Rivera, it’s difficult to say if his hope for Marisol is any more ungrounded than what he’s telling us about the outside world. It comes through in Frazel’s performance, as he goes from being manic when talking about Marisol to cerebral and other-world when describing the industrial plant across the street.

Two other performances worth seeing follow the intermission. The first is Zoe Rosenfeld as a hysterical (in both senses of the word) woman in furs, who went over her credit limit and was sent to live on the streets. As an upper-class woman who has been reduced to nothing along with much of the rest of the world, she aggressively threatens Marisol in the hope of getting her her CityBank Mastercard reestablished. The second is a tripped out dude played by Jeremiah True, who enters the stage on a wheelchair stacked high with trash bags to ruminate on the moon and discuss his relationship with his own guardian angel with Marisol. His role, as a scarred man who was subjected to blind hate, makes a him a sort of homeless mystic, the type of guy who you could see wandering through city parks alone, but perverted by a world that has also lost its bearings.

Through much of the second half of the play the versatility of the blackbox theatre is very evident. Rubble, trash and huddled people in blankets litter the stage and the before the industrial backdrop. The sound and lighting also showcased the capabilities of the new space, making the room reverberate with the echoes of the war in heaven and the flashes and screams of neo-Nazi warfare in New York. The play creates a more immersive experience than any other play I’ve seen while at Reed. At times powerfully surreal and at others absurdly hilarious, it is certainly a play to see.