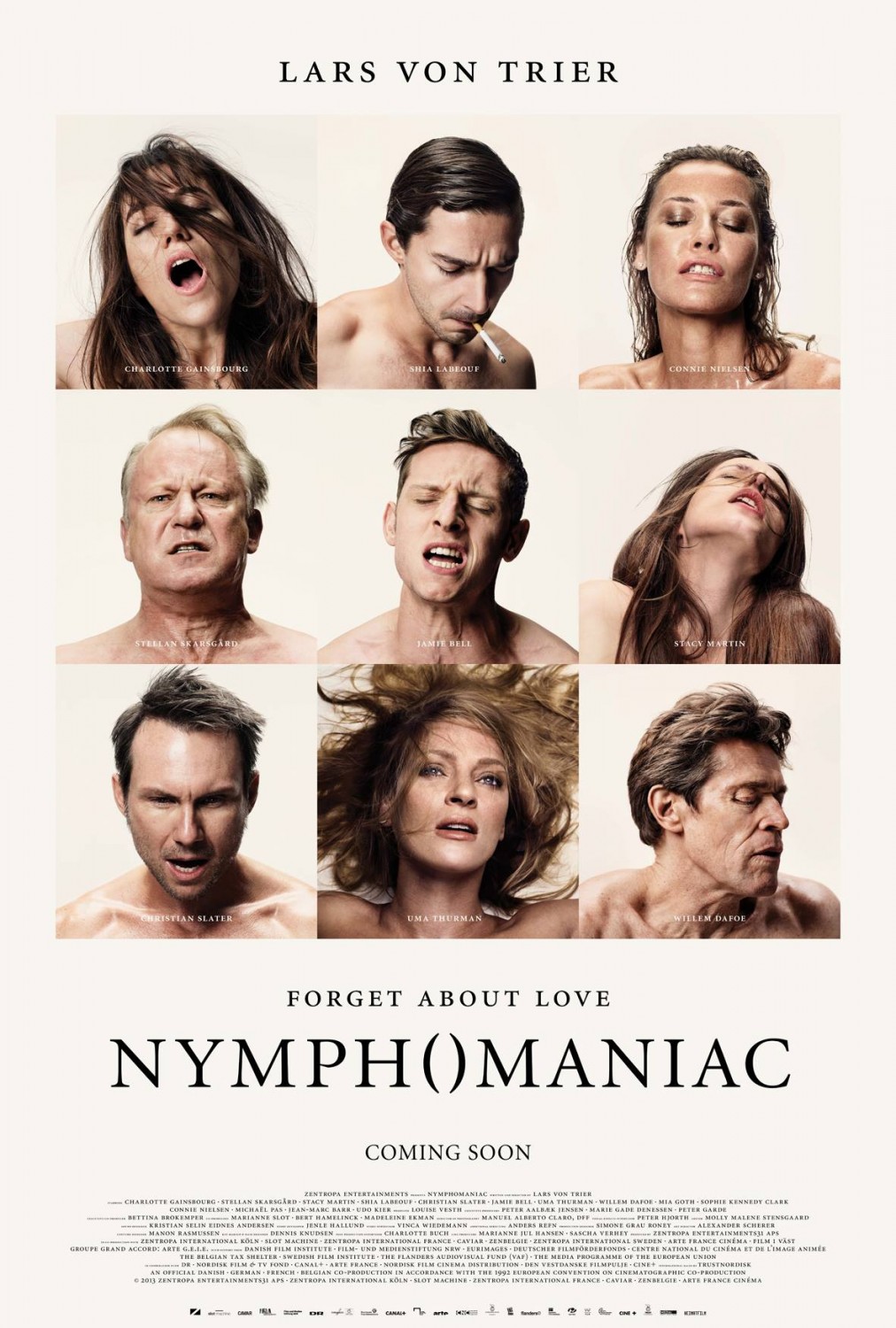

“Nymphomaniac”, Lars von Trier’s most recent film, begins with Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) battered and left in an alleyway to be discovered by Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), who takes her in into his home. There, Joe begins to recount the sexual antics that led to her destitution.

The films that make up Lars von Trier’s ‘Depression Trilogy’—“Antichrist”(2009), “Melancholia” (2011), and now “Nymphomaniac”— pose problems for potential analysis and assessment. “Antichrist” features recurring themes from past efforts of von Trier: a manic female lead (Breaking the Waves (1996), Dancer in the Dark (2000)), explicit sex (The Idiots (1998)) and possible infanticide (Medea (1988)). Looking deeper into the movie’s themes, however, it’s hard to not get caught up on the homages that von Trier makes to films by his auteur heroes Andrei Tarkovsky—to whom the whole trilogy is dedicated — Ingmar Bergman, and arguably, Pier Pasolini.

The setting of the edenic cabin is straight out of Tarkovsky’s “The Mirror” (1975), although it also references the Zone in another of Tarkovsky’s films, “Stalker” (1979). Joe’s gradual descent into a world of evils is reminiscent of Pasolini’s “Salò” (1975), and the chapter headings of “Nymphomaniac” seem to strengthen this comparison. In contrast, “Melancholia” has the combined subplots of Tarkovsky’s “Solaris” (1972) and “The Sacrifice” (1986) mixed with many from Bergman’s “Persona” period (1966).

What I am trying to point out here is that an analysis of von Trier’s trilogy is almost impossible without delving into his blatant references to other films. Once it has been evaluated how much of these three films is supported by seemingly stolen plots and themes, it becomes quite hard to evaluate them in their own right, outside of giving praise for their seamless appropriation of other masters’ styles and stories. “Nymphomaniac” takes this a step further than the previous two films, in that von Trier’s new production whirls through completely unassociated frameworks at a mile a minute, makes ironic gestures at the aforementioned directors’ projects, and restricts itself from taking its main story seriously. It’s a nightmare to assess.

With the wooden delivery of a renunciation of religion by the main players, Charlotte Gainsbourg and Stellan Skarsgård, the trudging four-hour film starts by throwing any grounding system of thought straight out the window. Is this a defense mechanism of von Trier’s against critics, to render any understanding of the film moot? Does he want us to wonder this? Naming Stellan’s erudite character ‘Seligman’ is a clear critique against the reasoning through aspect of psychoanalysis, a trait shared by Dafoe in “Antichrist” and Sutherland in “Melancholia”. But is this relation to the rest of the trilogy a serious one, or is von Trier toying with our analytic instinct?

The acting in the Gainsbourg-Skarsgård arc is painfully awkward and forced. If this were not purposeful, at least to some degree, then von Trier would have just released the biggest flop of his career. I am giving him the benefit of the doubt here. As a contrast, I do not think that LaBeouf’s disgusting British accent is on purpose, nor is Stacy Martin’s inability to take the stage. Also the shittiness and shiftiness of the majority of this film’s subplots does seem to be intentional. Maybe it is just a sorry hope that it is something more than an ironic joke.

There is much to talk about after one has seen the film. Engage me in a dialogue if you see me on campus. And by the way, watch the two parts back-to-back. I tried waiting a bit between them and it was a horrid idea.